.

For Nicole Killian’s 2018 Spring Seminar I created this speculative season newspaper designed to be a takeaway for ballet fans, or balletomanes as they are called in the dance world. It’s loosely based off The Australian Ballet’s Balletomane newspaper series which my Australian friends save and send to me.

THE NEOCLASSICAL NEWSPAPER

New York City Ballet 2018/19

POET TO BALLERINA

My verses cannot comment

on your immortal moment,

or tell you what you mean;

only Balanchine

has the razor edge,

and knows the art of language

- Robert Lowell, 1961 (1)

New York City Ballet will open the 2018/19 season with George Balanchine’s Agon, and The Four Temperaments, commemorating his reinvention of classical ballet. The featured repertory showcases the new and timely narratives that Balanchine evoked when he replaced ballet’s standard fairytale drama with a new drama born of pure, exaggerated form.

Join us in celebrating the abstraction and subversion that this iconic choreographer brought to the stage.

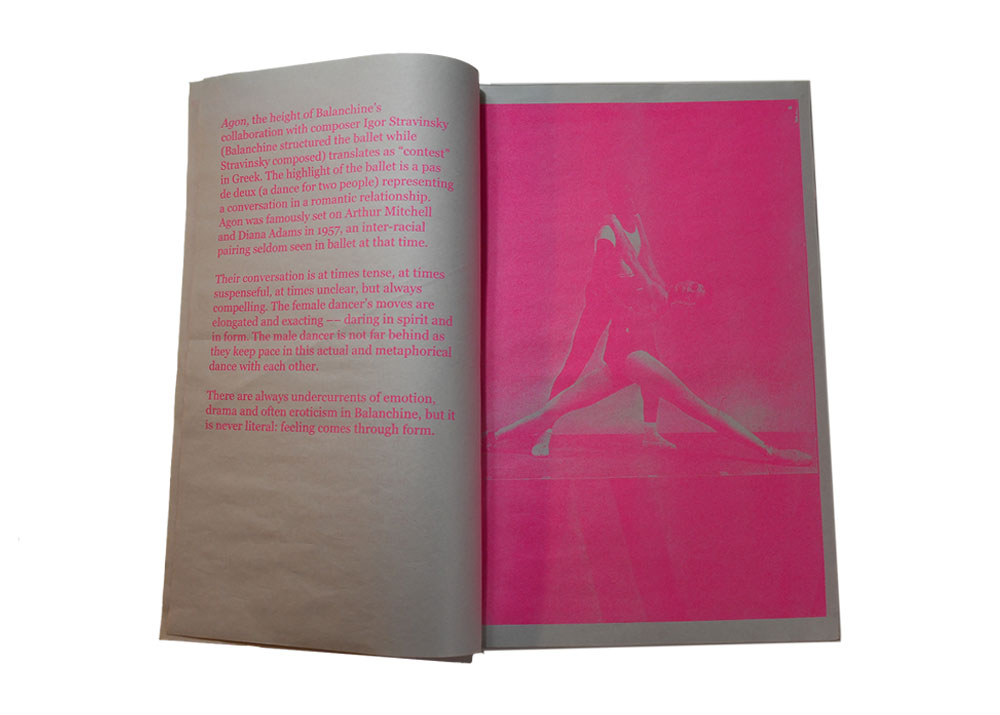

“There are always undercurrents of emotion, drama and often eroticism in Balanchine, but it is never literal: feeling comes through form.” (2)

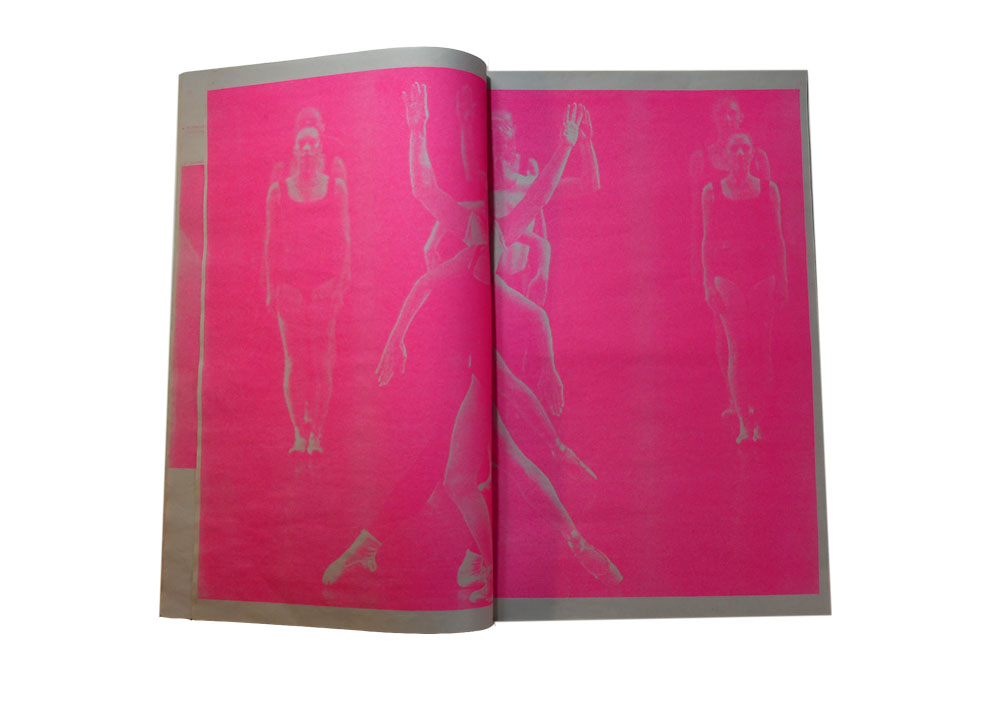

Agon, the height of Balanchine’s collaboration with composer Igor Stravinsky (Balanchine structured the ballet while Stravinsky composed) translates as “contest” in Greek. The highlight of the ballet is a pas de deux (a dance for two people) representing a conversation in a romantic relationship. Agon was famously set on Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams in 1957, an inter-racial pairing seldom seen in ballet at that time.

Their conversation is at times tense, at times suspenseful, at times unclear, but always compelling. The female dancer’s moves are elongated and exacting –– daring in spirit and in form. The male dancer is not far behind as they keep pace in this actual and metaphorical dance with each other.

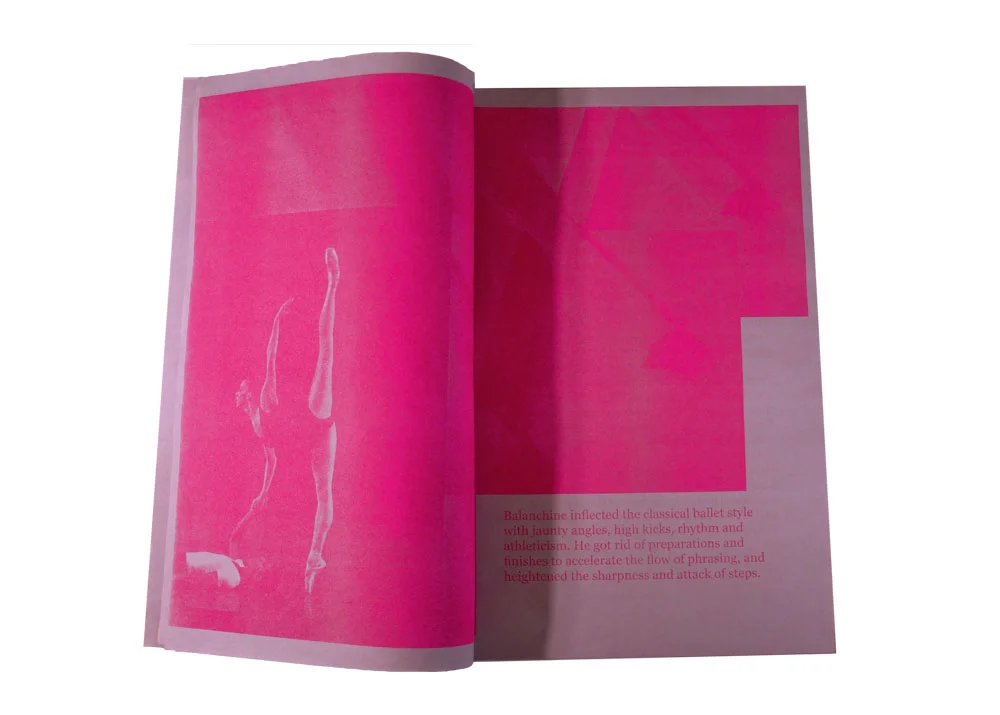

“Balanchine inflected the classical ballet style with jaunty angles, high kicks, rhythm and athleticism. He got rid of preparations and finishes to accelerate the flow of phrasing, and heightened the sharpness and attack of steps.” (2)

Together these fast-paced, angular movements create harmony and illusion.

At the premiere of Balanchine’s The Four Temperaments, famed critic Edwin Denby recalled sitting “spellbound by the constant surprise of the dance development, by the denseness and power of the dance images.” (3)

Though the work references the medieval concept of psychological humors, it is most closely associated with the striking movement language that Balanchine created in synthesis with Paul Hindemith’s original score for the work – Theme with Four Variations [According to the Four Temperaments] for string orchestra and piano, 1940)

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s synopsis of the one portion of the work reads, “Legs kick high, then slam down with pointes piercing the floor and pelvises thrusting forwards with menace. It’s an army of women blocking the pathway of a hapless, isolated male. Meanwhile, a spatial process is in operation, small- and large-scale; it is carved around individual bodies or embraces the edges of a vast arena, and finally drives an aeroplanes-taking-off-from-a-runway apotheosis.” (3)

“A ballet may contain a story, but the visual spectacle, not the story is the essential element. The choreographer and the dancer must remember that they reach the audience through the eye — and the audience, in its turn, must train itself to see what is performed upon the stage. It is the illusion created which convinces the audience, much as it is with the work of a magician. If the illusion fails, the ballet fails, no matter how well a program note tells the audience that it has succeeded.” – George Balanchine (4)

Esteemed choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa echoes this sentiment, “Classical ballet was very much directed toward the audience. Neoclassical started to change the shapes but was still toward the audience. With contemporary ballet, you turn the room. The audience is asked to look at what is happening between the dancers. But it still uses the classical vocabulary and the aesthetic of a beautiful line.” (5)

A dancer in a Balanchine ballet carves and cuts through the space – athletically, precisely, and impossibly in time with the music.

“Make a novel a dance, I might as well have been saying, but I did not yet know this, nor would I know it now, had I never seen New York City Ballet. I remember the first time I did see it, leaning forward transfixed, excited in a way I had never expected. I remember thinking again and again of a line from a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins, a poem I rarely remembered and a line that had no application except in its rhythm, in the sharp clarity of its verb and the cool irony of its second clause: ‘Honour is flashed off exploit, so we say.” This was not spectacle, this was not costume, this was not ‘story.’ This was different. This was dance as a thing made, an object that showed the hand of its maker. This was the kind of dance that did everything I wanted to do myself. It had the speed, it had the clarity, it had set for itself the most difficult possible task, the impossible exercise. You could see the exercise. You could see the technique, you could see how it worked, you could see the blind devotion to making it work. Balanchine, I later read, called himself a cook, a gardener, a tailor, a craftsman. So we say.” – Joan Didion after Lincoln Kirstein brought her to see Serenade. (1)

WE ASKED A FEW DANCERS WHAT IT IS LIKE TO DANCE THESE WORKS:

“We … climbed through the walls of balletic convention to discover a whole new place to inhabit.” – Suzanne Farrell (6)

“The arms aren’t one unit, but many pieces in motion, responding to the air.” - Suki Schorer (7)

“Balanchine disguised all his preparations. He tried to make the in-between stuff look just as fantastic as the bigger steps.” NYCB principal Teresa Reichlen (7)

“I remember a flaxen-haired woman dancing the second trio in Balanchine’s Agon as two men elegantly clapped out the beats of her castanet solo behind her, feeling as if I’d been struck by lightning.” – Wendy Whelan (8)

Dance critic Arlene Croce talks about Balanchine’s style, as he developed it with one of his many great muses, Suzanne Farrell, in an illustrative and true way: “What they produced together through this system (of rehearsing Don Quixote) was something new, which Farrell calls off-center dancing, where the foursquare horizontal/vertical of the academic ballet technique is thrown off kilter, tilted, made dangerous and dynamic. Actually, other Balanchine dancers before Farrell had done off-center dancing. All his professional life Balanchine had been going after this look: it was his heritage from his youth in the Petrograd avant-garde of the Twenties, and it corresponded to the spirals and helices and flying arcs of his constructivist coevals. Indeed, it can be said to be their dance equivalent. It was part of a shared idea of beauty—pure energy, clean lines, no ballast—born of the early century. (6)

To talk about Balanchine one must end with critic Edward Denby whose life’s work included covering, and falling in (intellectual) love with, Balanchine.

“In The Divine Comedy Dante creates an image in only a few clear sharp lines and then changes the subject before you lose the image. The ability to do that in dance is just as extraordinary as achieving the same effect in poetry—to change the whole look of the stage…without making the viewer painfully aware of what is happening. Balanchine does this constantly … ” (9)

BALANCHINE’S MINIMALIST PALETTE

“Balanchine did not want to have scenery on stage that looks always the same. He came to prefer the stage to be a space simply filled by the dancers, with its appearance varied by changing their disposition upon it. Balanchine invented ‘the uniform’ – the way of dressing dancers in plain tights that was at first taken to be necessitated by poverty but is now accepted everywhere as a way of showing the dance. His achievement was that he imposed the classroom: he brought his classical tradition with him and insisted on revealing the school of classical dancing.” - Lincoln Kirstein. Kirstein met Balanchine in London in 1933, and upon seeing his ballets, invited him to work in the United States where they co-founded the School of American Ballet and New York City Ballet. (4)

These stark ballets evoked a profound cultural context. “In The Four Temperaments, Agon (1957) and Episodes (1959), Balanchine’s most celebrated “leotard” ballets of the time, that present was partly a metaphor for postwar New York. All three unfolded in a landscape of anxiety: they were anguished and sexually charged, with rhythms borrowed from jazz and percussive movements from modern dance, and matings fraught with loneliness, empty pleasure and erotic tension.” (1)

Untitled

To make even the body propose profundity.

Whatever beauty it has, as flesh, simple

meat, there is a sense that prolongs what

for the most part might be considered

ephemeral. That is, a performance, stops.

Unlike the demon Guttenberg produced.

But the dance, and what I have seen at the

Center especially, proposes that performance

Is an artifact, as well as anybody’s printed word

or hacked up metal.

What they have called “Twelve Tone Night” is

alone enough dance for most of us. (What do

we deserve?) The Pas de Deux in Agon is more

dance than we deserve. And it is an artifact of

constant vitality, even hidden and quiet in my

mind.

- Amiri Baraka. This poem was discovered

in a carton in the fifth-floor attic “motor room”

of the New York State Theater (1)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Photos are by Paul Kolnick for New York City Ballet with the exception of Arthur Mitchell and Diana Adams in "Agon" which is from Columbia University’s archives.

1) Ramsey, Christopher with New York City Ballet, Tributes: Celebrating Fifty Years of New York City Ballet, William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1998

2) Author not specified, Step-by-step guide to dance: George Balanchine, The Guardian, Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2009/jul/30/dance-george-balanchine, 2009

3)Thomas, Jeanie (notes) with editing by Fullington, Doug, The Four Temperaments, Retrieved from https://www.pnb.org/repertorylist/the-four-temperaments/, 2009.

4) Author not specified, Remembering Balanchine, BBC World Service, Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/arts/highlights/000823_balanchine.shtml, 2000

5) Perron, Wendy, What Exactly is Contemporary Ballet, Dance Magazine, Retrieved from https://www.dancemagazine.com/what_exactly_is_contemporary_ballet-2306944842.html, 2014

6) Accolla, Joan, Dancing for Balanchine, The New York Review of Books, Retrieved from http://www.nybooks.com/articles/1990/10/11/dancing-for-balanchine/, 1990

7) Author not specified, Dancing Balanchine, Dance Spirit, Retrieved from https://www.dancespirit.com/dancing-balanchine-2326223886.html,

8) Whelan, Wendy, Wendy Whelan: The First Time I Danced a Balanchine Ballet (the Day he Died), The New York Times, Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/23/arts/dance/wendy-whelan-the-first-time-i-danced-a-balanchine-ballet-the-day-he-died.html, 2017

9) Fuhrer, Margaret, Denby and Balancine: A Dance Critic’s Work, The Brooklyn Rail, Retrieved from: https://brooklynrail.org/2008/07/dance/denby-and-balanchine-a-dance-critics-work, 2008